Hospital Episodes Due to Antidepressant Overdose: An Under-Utilised Source of Pharmacovigilance Data

Abstract

Background:

Antidepressant agents are commonly implicated in drug overdose, and the toxicological profile varies between agents. Clinical data concerning overdoses are not systematically sought or evaluated in pharmacovigilance. The present study sought to examine the feasibility of collecting Emergency Department data concerning antidepressant overdose.

Methods :

Presentations to York Hospital due to intentional antidepressant overdose were studied between 2010 and 2011. Data collected were the type of antidepressant, dose, co-ingested drugs, duration of hospital stay, and need for critical care. Community National Health Service prescription data were evaluated across York and North Yorkshire region.

Results :

There were 250 overdose episodes. These involved a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) in 183 (73.2%), and a tricyclic in 45 (18.0%), equivalent to 24 episodes per 100,000 prescription items (95% CI 21-28 per 100,000) and 11 per 100,000 (8-15 per 100,000) respectively (P<0.0001). Citalopram was the most commonly prescribed, and associated with 22 overdose episodes per 100,000 (17-27 per 100,000). Fluoxetine was associated with 32 overdose episodes per 100,000 (24-41 per 100,000) (P=0.032 versus citalopram), whereas the lower rates were observed for amitriptyline (13, 9-17 per 100,000) (P=0.004) and dosulepin (2, 0-10 per 100,000) (P=0.001).

Conclusions :

A higher than expected number of overdose episodes involved an SSRI based on National Health Service primary care prescribing, and fewer episodes involved a tricyclic antidepressant. Clinical outcomes differed between agents, indicating the feasibility of using Emergency Department data to detect different patterns of toxicity between antidepressants. Further work is required to examine whether systematic collection of clinical toxicology data might enhance existing pharmacovigilance systems.

Author Contributions

Academic Editor: Satheesh Podaralla, Research Scientist : Formulation R&D SRI International Menlo Park, CA

Checked for plagiarism: Yes

Review by: Single-blind

Copyright © 2013 Cooke MJ, et al.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Citation:

Introduction

Intentional drug overdose is an important cause of Emergency Department attendances in the United Kingdom and elsewhere 1. Antidepressant agents are commonly implicated in drug overdose, and may result in significant morbidity and mortality 2, 3. Clinical outcomes after intentional antidepressant overdose vary substantially depending on the type of agent involved and dose ingested. For example, monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) ingestion can result in accumulation of norepinephrine within the central nervous system, and may cause profound haemodynamic instability, seizures, coma and death 4, 5. Tricyclic antidepressants are capable of blocking sodium channel conductance such that overdose is characterised by the occurrence of life-threatening arrhythmia, severe hypotension, generalised seizures, coma, and death 6, 7. In contrast, overdose involving a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) is characterised by less overall toxicity, fewer life-threatening complications, and a lower mortality than that attributed to MAOI or tricyclic antidepressants 8, 9, 10.

In recent years, there has been a trend towards increase antidepressant prescribing due widened clinical indications for pharmacological treatment. Prescribing patterns have changed such that MAOIs and tricyclic antidepressants are less widely relied upon, and there has been a substantial increase in the use of SSRIs and novel agents including duloxetine, mirtazapine, and venlafaxine 11, 12. These changes have been prompted by several factors, recommendations in clinical guidelines, adverse effect profile of specific drugs, marketing activity by the pharmaceutical industry, patient preference, and the perceived risk of self-harm in individual patients. Many existing pharmacovigilance systems have been designed to allow collection of data concerning medications used in accordance with the Marketing Authorisation, namely adverse effects arising from intended therapeutic use including prescribed dosages. In contrast, data concerning adverse outcomes in the setting of intentional drug overdose is not collected in a systematic manner, and these data tend to emerge as individual case reports, published case series, and abstracts at scientific meetings. Comparatively few data are collected systematically in this patient group, and there is a need for a better understanding of the link between exposure and extent of exposure to particular drugs and clinical outcomes. The present study sought to examine the possibility of using Emergency Department data to identify patterns of antidepressant overdose with respect to prevailing prescribing practices, and to evaluate clinical outcomes between specific agents as a measure of toxicity.

Methods

Clinical Data

York Hospital serves a semi-rural population of around 350,000 people in York and the North Yorkshire region, and receives approximately 70,000 Emergency Department attendances annually. This includes almost 900 attendances due to intentional drug overdose (1.3%) 13. Adults that present after drug overdose may be discharged home after completion of medical and psychiatric assessment, or admitted to the Acute Medical Unit if ongoing medical treatment is required or the patient is too drowsy or intoxicated to allow detailed psychiatric assessment. Patients may be admitted to a critical care area if there is severe haemodynamic disturbance or if non-invasive or invasive ventilatory support may be required. The study population consisted of all patients aged ≥16 years that presented to the Emergency Department due to drug overdose between January 2010 and December 2011 inclusive. Data collected were age, gender, date and time of ingestion, type of agent ingested, dose, co-ingested drugs and ethanol, admission to hospital, duration of hospital stay, and if transfer to a critical care area was required.

Prescribing Data

National Health Service primary care prescribing data in York and North Yorkshire region are routinely collected and examined for the purposes of evaluating prescribing trends and variance by prescribers across a wide range of therapeutic areas. The database was interrogated for all prescriptions items for antidepressant agents in 2010 and 2011. Antidepressants were classified as a tricyclic, SSRI, or other antidepressant in accordance with the categories listed in the British National Formulary 14.

Data Analyses

Data concerning specific antidepressant agents was considered as a proportion of all overdose episodes or prescribing items. Overdose episodes were expressed per 100,000 prescription items, and comparison made between agents using Chi square proportional tests. The ingested dose was expressed as a multiple of the World Health Organization ‘Defined Daily Dose’ (DDD) to allow comparison between agents 15. Analyses were performed using MedCalc statistical software v.9.1.0.1 (MedCalc, Mariakerke, Belgium), and P-values <0.05 were accepted as statistically significant 16.

Results

There were 1092 Emergency Department attendances due to intentional drug overdose, including 250 episodes that involved an antidepressant (22.9%). The median age was 37 years (population range 16-85 years), and there were 165 women (66%) (Table 1). Hospital presentations involved an SSRI in 183 (73.2%), a TCA in 45 (18.0%), and another antidepressant in 22 (8.8%). Patients that ingested a TCA were more likely to require admission to hospital, had a longer duration of hospital stay, and were more likely to require transfer to a critical care area (Table 1). One death occurred in a 34-year-old woman with a past history of chronic alcohol excess that presented to hospital due to asystolic cardiac arrest after overdose involving unknown quantities of escitalopram, paracetamol, and codeine. Patterns of antidepressant overdose in men and women are presented in Table 2.

Table 1. Summary characteristics of patients presenting after intentional antidepressant overdose presented as median (interquartile range) and proportions.| SSRI n=183 | Tricyclic Anti-depressantn=45 | Other Anti-depressantsn=22 | |

| Women | 132 (72.1%) | 24 (53.3%) | 9 (40.9%) |

| Men | 51 (27.9%) | 21 (46.7%) | 13 (59.1%) |

| Age (years) | 35 (22-47) | 37 (30-44) | 38 (30-47) |

| Alcohol co-ingestion | 71 (38.8%) | 22 (48.9%) | 11 (50.0%) |

| Other drug co-ingestion | 127 (69.4%) | 33 (73.3%) | 19 (86.4%) |

| Drug dose as DDD multiple | 14 (3-31) | 7 (0-22)** | 15 (0-37) |

| Hospital admission | 102 (55.7%) | 39 (86.7%)† | 15 (68.2%) |

| Critical care admission | 3 (1.6%) | 7 (15.6%)†† | 0 (0.0%) |

| Duration of hospital stay (days) | 1 (1-1) | 2 (1-4)* | 1 (1-2) |

| Women n=183 | Men n=45 | |

| SSRI | 132 (80.0%, 66.9-94.9%) | 51 (60.0%, 44.7-78.9%) |

|---|---|---|

| Citalopram | 57 (34.6%) | 26 (30.6%) |

| Fluoxetine | 38 (23.0%) | 15 (17.7%) |

| Venlafaxine | 15 (9.1%) | 4 (4.7%) |

| Sertraline | 15 (9.1%) | 4 (4.7%) |

| Escitalopram | 4 (2.4%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Paroxetine | 3 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Tricyclics | 24 (14.6%, 9.3-21.6%) | 21 (24.7%, 15.3-37.8%) |

| Amitriptyline | 22 (13.3%) | 17 (20.0%) |

| Lofepramine | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (1.2%) |

| Clomipramine | 1 (0.6%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Dosulepin | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.4%)* |

| Imipramine | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.2%) |

| Others | 9 (5.5%, 2.5-10.4%) | 13 (15.3%, 8.1-26.2%) *** |

| Mirtazapine | 8 (4.8%) | 12 (14.1%)** |

| Duloxetine | 1 (0.6%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Trazodone | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.2%) |

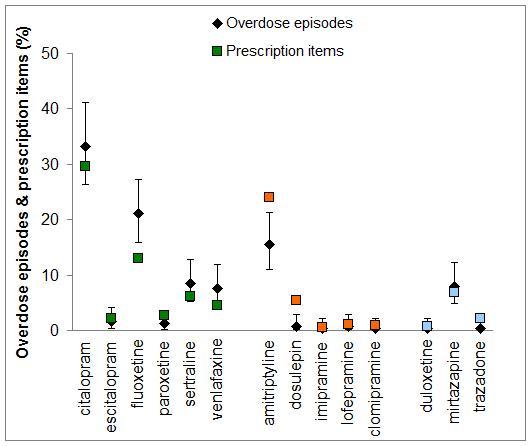

There were 1,304,795 prescription items for antidepressants in the York and North Yorkshire region, and these included 749,144 (57.4%) items for a SSRI, 427,127 (32.7%) for a TCA, and 129,243 (9.9%) others. The overall occurrence of antidepressant overdose was equivalent to 19 episodes per 100,000 prescription items (95% CI 17-22 per 100,000 scripts). A higher number of overdoses were observed in the SSRI group compared to the TCA group: 24 (95% CI 21-28) versus 11 (95% CI 8-15) respectively (P<0.0001). Citalopram was the most widely prescribed, and used as a reference comparator (Table 3). Fluoxetine was associated with a higher number of overdose episodes: 32 per 100,000 scripts (24-41) versus 22 (17-27) respectively (P=0.032). Fewer than expected overdose episodes involved amitriptyline (13, 95% CI 9-17, P=0.004) and dosulepin (2, 95% CI 0-10, P=0.001) (Figure 1).

Table 3. Antidepressant overdose episodes and community prescription items in 2010-2011.| Antidepressant | Prescription items | Overdose episodes | Episodes per 100,000 scripts | Likelihood ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSRIs | |||||

| Citalopram | 380640 | 83 | 22 (17-27) | 1.00 | - |

| Escitalopram | 27393 | 4 | 15 (4-37) | 0.67 | 0.25-1.80 |

| Fluoxetine | 167096 | 53 | 32 (24-41) | 1.45* | 1.03-1.22 |

| Paroxetine | 35479 | 3 | 9 (2-25) | 0.39 | 0.12-1.22 |

| Sertraline | 79807 | 21 | 26 (16-40) | 1.21 | 0.75-1.95 |

| Venlafaxine | 57784 | 19 | 33 (20-51) | 1.51 | 0.92-2.48 |

| All SSRIs | 748199 | 183 | 24 (21-28) | ||

| TCA’s | |||||

| Amitriptyline | 310123 | 39 | 13 (9-17) | 0.58** | 0.39-0.84 |

| Clomipramine | 11047 | 1 | 9 (0-5) | 0.42 | 0.06-2.98 |

| Dosulepin | 69579 | 2 | 3 (0-10) | 0.13** | 0.03-0.54 |

| Imipramine | 6321 | 1 | 16 (0-9) | 0.73 | 0.10-5.21 |

| Lofepramine | 15042 | 2 | 13 (2-5) | 0.61 | 0.15-2.48 |

| All TCA’s | 412112 | 45 | 11 (8-15)† | ||

| Others | |||||

| Duloxetine | 9883 | 1 | 10 (0-56) | 0.46 | 0.06-3.33 |

| Mirtazapine | 88705 | 20 | 23 (14-35) | 1.03 | 0.63-1.68 |

| Trazodone | 28729 | 1 | 4 (1-19) | 0.16 | 0.02-1.15 |

| All others | 127317 | 22 | 17 (11-26) | ||

| All antidepressants | 1287628 | 250 | 19 (17-22) |

Figure 1.The proportion of overdose episodes related to specific antidepressant agents, expressed as percentage of all episodes with 95% confidence intervals; the corresponding community prescriptions are expressed as a percentage of all antidepressant prescription items.

Discussion

Around five and a half thousand deaths were attributed to drug poisoning in England and Wales alone in 2010-2011, and antidepressants account for a high proportion of these. The age-standardised annual mortality rates attributed to antidepressant overdose are 7.1 (95% CI 6.1-8.1) and 6.7 (95% CI 5.8-7.6) per million in men and women respectively, which are almost double those attributed to paracetamol poisoning of 3.1 (2.4-3.7) and 3.6 (3.0-4.3) deaths per million in men and women respectively 17. Within these deaths, differences exist between agents as a result of variations in their accessibility and inherent toxicity 18. Citalopram was the most widely prescribed antidepressant and most likely to be implicated in overdose, despite mounting data that it is capable of prolonging the QT interval and may predispose to arrhythmia 19, 20. The fatal toxicity index has been proposed as a measure that takes account of the number of prescription items and, for example 21. This indicates between 11 and 35 deaths per million antidepressant prescription items, including 27 to 47 deaths per million amitriptyline prescription items 22, 23. An alternative approach has been to consider the case fatality, expressed as a ratio of fatal to non-fatal self-poisonings; the case fatality has been reported for tricyclic antidepressants and SSRIs as 13.8 (95% CI 13.0-14.7) and 0.5 (95% CI 0.4-0.7) respectively (P<0.0001) 24. Only one death was observed in the present study, equivalent to 0.8 deaths per million prescription items (95% CI 0.0-4.3 deaths per million), indicating that only a very small proportion of antidepressant poisoning deaths occur in hospital.

As expected, the present findings indicate that overdose involving tricyclics was associated with a greater need for hospital admission, longer hospital stay, and greater need for critical care compared to overdose involving SSRI or other antidepressants. These observations may be explained as a result of differing intrinsic toxicity because the ingested dose was comparatively smaller in the tricyclic group, and there were no significant differences in co-ingested drugs and ethanol 25. Previous reports indicate that intentional overdose involving MAOI or tricyclic antidepressants may result in severe arrhythmia and prolonged generalised seizures that are resistant to conventional therapy 26. In contrast, overdose involving SSRIs may provoke dose-dependent generalised seizures in around 10%, and these are usually self-limiting or promptly terminated by benzodiazepine administration 27. SSRI poisoning gives rise to prolongation of the QT interval in around 5% of patients, but the occurrence of life-threatening cardiac arrhythmia is thought to be very rare 28, 29.

The study design did not directly address the factors that might give rise to preferential involvement of particular drugs amongst patients that attend hospital after intentional overdose, and a number of possible explanations exist. Firstly, a high level of awareness of the comparative toxicity of various antidepressant agents and judicious prescribing would result in greater reliance upon SSRI agents, and less reliance upon tricyclic or MAOI agents when issuing prescriptions to patients that are considered to be at increased risk of self-harm. Secondly, the tendency towards increasing antidepressant use coupled with SSRIs being relied upon as first-line treatment means that a greater number of ‘low risk’ patients will receive an SSRI, and this group may be more likely to seek medical attention after intentional overdose. Thirdly, tricyclic antidepressants may be prescribed where SSRI treatment has failed, demarcating a subset of patients with more resistant or severe depressive illness that may be less inclined to seek medical attention after overdose. Fourthly, tricyclic antidepressants may have been initiated in the past, and used to maintain long-term remission of symptoms, and this patient subgroup may be less likely to exhibit self-harm behaviour. Lastly, tricyclics may be more likely to be used for disorders such as neuropathic pain, where the risk of intentional overdose is expected to be lower.

Conclusions

SSRIs were more highly represented amongst overdose patients than might have been predicted from the numbers of prescription items, whereas fewer episodes involved a tricyclic antidepressant. These data suggest a preferential use of SSRI rather than tricyclic antidepressants in patients at risk of self-harm. Further work is required to understand the factors that influence antidepressant prescribing so as to minimise the risk of harm in this at-risk patient population. These findings indicate that Emergency Department data are sufficiently sensitive to detect different clinical outcomes between antidepressant agents in overdose. These data may make a useful addition to the existing sources that are relied upon in conventional pharmacovigilance programmes. Further work is required to explore the feasibility of systematic clinical data collection and how these data might be used to inform prescribers in order to minimise adverse outcomes in patients at high risk of self-harm.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jackie Snowden, York Hospital for assistance with retrieval of the case notes to enable data collection and analyses.

References

- 1.Waring W S, McGettigan P. (2011) Clinical toxicology and drug regulation: A United Kingdom perspective. , Clin. Toxicol 49, 452-456.

- 3.Waring W S. (2012) Clinical use of antidepressant therapy and associated cardiovascular risk. Drug Healthc. Patient Saf. 4, 93-101.

- 4.Sarko J. (2000) Antidepressants, old and new. A review of their adverse effects and toxicity in overdose. , Emerg. Med. Clin. North Am 18, 637-654.

- 6.C F Koegelenberg, Z J Joubert, E M Irusen. (2012) Tricyclic antidepressant overdose necessitating ICU admission. , S. Afr. Med. J 102, 293-294.

- 7.Levine M, D E Brooks, Franken A, Graham R. (2012) Delayed-onset seizure and cardiac arrest after amitriptyline overdose, treated with intravenous lipid emulsion therapy. Pediatrics. 130,e 432-e 438.

- 8.G K Isbister, S J Bowe, Dawson A, I M Whyte. (2004) Relative toxicity of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in overdose. , J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol 42, 277-285.

- 9.C A Kelly, Dhaun N, W J Laing, F E Strachan, A M Good. (2004) Comparative toxicity of citalopram and the newer antidepressants after overdose. , J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol 42, 67-71.

- 10.R J Flanagan. (2008) Fatal toxicity of drugs used inpsychiatry. Hum.Psychopharmacol.23(Suppl1) 43-51.

- 11.Wong A, D M Taylor, Ashby K, Robinson J. (2010) Changing epidemiology of intentional antidepressant drug overdose in Victoria. , Australia. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 44, 759-764.

- 12.Bergen H, Murphy E, Cooper J, Kapur N, Stalker C. (2010) A comparative study of non-fatal self-poisoning with antidepressants relative to prescribing in three centres in England. , J. Affect. Disord 123, 95-101.

- 13.N J James, Hussain R, Moonie A, Richardson D, Waring W S. (2012) Patterns of admissions in an acute medical unit: priorities for service development and education. , Acute Med 11, 74-80.

- 14.JointFormularyCommittee.British National Formulary (online) London:. BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press http://www.medicinescomplete.com Accessed on 05thDecember2012 .

- 15.T M Armstrong, M S Davies, Kitching G, Waring W S. (2012) Comparative drug dose and drug combinations in patients that present to hospital due to self-poisoning. Basic Clin. , Pharmacol. Toxicol 111, 356-360.

- 16.Schoonjans F, Zalata A, C E Depuydt, F H Comhaire. (1995) MedCalc: a new computer program for medical statistics. , Comput. Methods Programs Biomed 48, 257-262.

- 17.The Office for National Statistics (ONS). (2011)Deaths related to drug poisoning in England and Wales,. Statistical Bulletin29/08/2012. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/index.html Accessed on 05thDecember2012

- 18.White N, Litovitz T, Clancy C. (2008) Suicidal antidepressant overdoses: a comparative analysis by antidepressant type. , J. Med. Toxicol 4, 238-250.

- 19.L E Friberg, G K Isbister, S B Duffull. (2006) Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modelling of QT interval prolongation following citalopram overdoses. , Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol 61, 177-190.

- 20.M J Cooke, Waring W S. (2012) Citalopram and cardiac toxicity. , Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol 69, 755-760.

- 21.J C Rose, A S Unis. (2000) A mortality index for postmarketing surveillance of new medications. , Am. J. Emerg. Med 18, 176-179.

- 22.J A Henry, C A Antao. (1992) Suicide and fatal antidepressant poisoning. , Eur. J. Med 1, 343-348.

- 23.N A Buckley, P R McManus. (1998) Can the fatal toxicity of antidepressant drugs be predicted with pharmacological and toxicological data. , Drug Saf 18, 369-381.

- 24.Hawton K, Bergen H, Simkin S, Cooper J, Waters K. (2010) Toxicity of antidepressants: rates of suicide relative to prescribing and non-fatal overdose. , Br. J. Psychiatry 196, 354-358.

- 25.Koski A, Vuori E, Ojanperä I. (2005) Newer antidepressants: evaluation of fatal toxicity index and interaction with alcohol based on Finnish postmortem data. , Int. J. Legal Med 119, 344-348.

- 26.Waring W S, Wallace W A. (2007) Acute myocarditis after massive phenelzine overdose. , Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol 63, 1007-1009.

- 27.Waring W S, J A Gray, Graham A. (2008) Predictive factors for generalized seizures after deliberate citalopram overdose. , Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol 66, 861-865.