The Effectiveness of Cognitive-Analytic Therapy in Women Diagnosed with Breast Cancer and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Abstract

The present study examines the effectiveness of Cognitive-Analytic Therapy (CAT) in women diagnosed with breast cancer and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) on reducing PTSD symptomatology and improving their mental health state (depression, self-esteem, post- traumatic growth, quality of life, therapeutic alliance). Additionally, the investigation includes the determination of the demographic, socio-economic and medical factors’ impact on mental health indicators in women with breast cancer and PTSD. The sample was 188 women with breast cancer and PTSD at the Chemotherapy Unit of ‘Agios Andreas’ General Hospital in Patras. The questionnaire data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistical analysis in order to determine any statistically significant correlations between the experimental and the control group and between psychological scales and the demographic and socio-economic factors. The findings confirm the effectiveness of CAT in women with breast cancer and PTSD in reducing PTSD and depressive symptoms, improving self-esteem and quality of life, achieving greater post-traumatic growth, and fostering a better therapeutic relationship with the therapist. The demographic, socio-economic and medical factors examined affected dissimilarly each psychological scale, as statistically significant associations were found with some scales but not with others.

Author Contributions

Academic Editor: Sasho Stoleski, Institute of Occupational Health of R. Macedonia, WHO CC and Ga2len CC

Checked for plagiarism: Yes

Review by: Single-blind

Copyright © 2026 Koutrouki Aikaterini, et al.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Citation:

Introduction

Epidemiological data show that breast cancer remains the most frequently diagnosed cancer among women globally in the 20-50 years old age group 1, 2 emphasizing the critical role of early diagnosis in significantly improving curability rates. Beyond its clinical impact, breast cancer imposes a substantial socioeconomic burden on the national healthcare system. Addressing this multifaceted challenge extends beyond the scope of oncology, as it constitutes a challenge for all specialties and services of a hospital and ultimately of the welfare state, such as social and psychological services as well as health disability certification committees.

The breast cancer diagnosis fundamentally alters a woman’s life serving as a critical turning point. It is characterized as a complex and profoundly stressful experience as a result of the severity of the diagnosis, the treatment plan, the prognosis and the potential side effects across physical, psychological, social and occupational domains. These challenges can significantly influence the treatment outcome and subsequent life after cancer. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) cancer is a major stressor capable of inducing PTSD 3. PTSD is defined as an anxiety disorder that can manifest following the experience or witnessing of a life-threatening event. Individuals experiencing cancer-related PTSD frequently present with comorbidities, including major depression, panic disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder, alongside physical issues such as sleep disturbances, substance abuse, hypertension, asthma, and chronic pain syndromes.

The development and severity of PTSD are not solely determined by the traumatic event itself but are significantly influenced by a complex interplay of sociodemographic, psychosocial, and biological factors 4, 5. According to the literature review, the results are conflicting regarding the predictive power of these factors for PTSD. Risk factors are not limited to socio-demographic data 6 but also incorporate pre-traumatic characteristics (pre-existing mental disorders, personality, and sleep quality), biological markers 5 and individualized medical histories (multiple traumas) as well as peri-/post-traumatic data (trauma severity, lack of social support) 7, 8, 9.

Effective management of the emotional reactions and psychological sequelae of cancer- related PTSD can be achieved through various therapeutic modalities, including both psychotherapeutic (individual and group) and pharmaceutical interventions. The general psychological treatment literature for breast cancer suggests that interventions with cognitive and behavioral elements can help improve quality of life, mood and psychological well-being 10. CAT is a short-term, individual psychotherapy that focuses on the early development of reciprocal roles and behavioral patterns, initially established and consolidated as functional, but over time they turned into rigid and dysfunctional, leading the patient to being trapped in ineffective patterns, choices and behaviors. Through the therapeutic process, the patient’s psychological traumas are revealed and healed equipping the patient with new tools of self-awareness and navigating life more effectively.

The effectiveness of CAT has been demonstrated across a broad spectrum of psychopathology. Extensive research supports its effectiveness in treating emotional and anxiety disorders (e.g., depression, phobias, panic disorder, social anxiety, and postpartum depression), personality disorders (particularly Borderline Personality Disorder), psychotic disorders during remission (e.g., schizophrenia), eating disorders, substance dependencies, divorce and psychological distress arising from physical illnesses such as multiple sclerosis 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16. This comprehensive empirical support highlights CAT's robust applicability as a versatile and effective psychotherapeutic modality.

Research aim and objectives

Despite the high prevalence of cancer-related PTSD among breast cancer survivors, clinical guidelines for its psychological management remain predominantly focused on traditional Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), modalities that may not fully address the relational trauma inherent in the cancer treatment medical experience where invasive treatments and shifts in body image activate maladaptive reciprocal roles 17. CAT is a theoretically well- suited approach to this context and systematic reviews confirm CAT’s efficacy in personality disorders and complex mental health presentations. However, outcome research remains sparse and largely confined to non-trauma populations 15 as, to date, no randomized controlled studies have examined the application of CAT for PTSD symptoms specifically for breast cancer patients 18.

This represents a critical research gap, and in the present research a quantitative cross- sectional feasibility study was designed and conducted aiming to investigate the effectiveness of CAT on reducing PTSD symptomatology and improving the mental health state of women diagnosed with breast cancer and PTSD (depression, self-esteem, post-traumatic growth, quality of life, therapeutic alliance). To achieve that, the following research objectives were developed: i) measurement of PTSD score in women with breast cancer before and after CAT treatment plan, as well as ii) measurement of their depression, self-esteem, post-traumatic growth levels, quality of life and of the therapeutic alliance, iii) investigation of the effect of socio-economic and clinical variables in these psychological markers (marital status, education attainment, employment status, place of residence, surgery, radiation therapy, breast reconstruction, age, parity) and iv) investigation of the correlation between the psychometric tools.

Methodology

Sample

The research sample comprised 188 women with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy at the ‘Agios Andreas’ General Hospital of Patras, Greece. Inclusion criteria mandated sufficient proficiency in the Greek language to complete psychometric tools and a minimum of one month post-diagnosis to allow for the development and reliable identification of potential PTSD symptoms, a timeframe consistent with the literature indicating the rarity of delayed-onset PTSD. Based on the chemotherapy treatment room, participants were randomly allocated into two groups: the experimental group (N=100) received care in Treatment Room A, while the control group (N=88) received chemotherapy in the smaller Treatment Room B. All participants provided informed consent, acknowledging the study’s purpose, and that anonymity and confidentiality would be protected. Any specific medical data, regarding the stage of breast cancer or previous mental health patient history, were not recorded or taken into consideration during analysis and results deduction of the present study. Although potentially impactful variables, such sensitive – and often unknown to the patient – clinical information was considered the exclusive domain of the treating oncologist, and could lead to arbitrary and potentially detrimental conclusions by the patients themselves, negatively affecting their treatment adherence and overall health condition.

Questionnaires & psychometric tools

To effectively achieve the study’s research aim a comprehensive list of psychometric scales were employed. They were selected based on their compatibility with measuring PTSD and its common comorbidities (depression, low self-esteem, post-traumatic growth and quality of life) and assessment of the therapeutic relationship. Specifically, the Greek version of the following international scales were used: a custom socio-demographic questionnaire, PTSD Check List – Civilian Version (PCL-C) 19, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) 20, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) 21, European Organization For Research and Treatment Of Cancer Quality of Life Group - EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3.0), Post-traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) 22, California Psychotherapy Alliance Scale (CALPAS) 23.

In the experimental group, the questionnaires were split across the first two CAT sessions in order to mitigate respondent fatigue: socio-demographic data, PCL-C and HAM-D during the first session, and RSES, PTGI and CALPAS during the second session. Respectively, the control group completed the scales during their first two cycles of chemotherapy. All participants, across both groups, were re-administered the scales after a 6- month period following the completion of the psychotherapy sessions or chemotherapy cycles. All questionnaires were completed at the hospital facility privately and without the researcher's presence. Furthermore, psychoeducation tools, such as the Psychotherapy Booklet and Rating Scale, were provided to all women undergoing psychotherapy sessions to support the intervention process.

Statistical analysis

The data collected from the psychometric questionnaires were processed and analyzed using a thorough statistical methodology including descriptive and inferential statistical analysis. For descriptive analysis, measures of central tendency and variability (such as minimum, maximum, mean, and standard deviation) were calculated and visualized using bar charts. The inferential analysis focused on exploring differences and relationships within the variables. Key hypothesis tests included the t-test for independent samples (and the Mann- Whitney test as a non-parametric alternative) to compare means between two independent demographic subgroups. For comparisons involving three or more subgroups, a One-way ANOVA (and the Kruskal-Wallis test as a non-parametric alternative) was utilized. A Paired- samples t-test was employed to investigate mean differences in the same group across two different time points. Furthermore, a Mixed Design ANOVA was used to assess the potential impact of the psychological intervention to the mental health indicators between the experimental and control groups. Finally, potential correlations between numerical and ordinal variables were explored using Spearman’s Rho coefficient. The internal consistency and reliability of the multi-item scales were assessed using Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient, with the minimum acceptable value being 0.70. A confidence level of α=0.05 was consistently used for all hypothesis testing.

Study limitations

While this study aims at yielding significant scientific insights, several methodological constraints merit consideration. Firstly, the voluntary nature of the participation in the study and the proactive engagement in regular medical screenings prior to their breast cancer diagnosis may introduce selection bias, suggesting that participants present higher intrinsic motivation, stronger predisposition toward psychological support and greater adherence to clinical protocols than the general patient population. Additionally, while self-report psychometric tools are widely used because they are practical and standardized, they may introduce the risk of subjective variances influenced by transient factors such as treatment- related fatigue or immediate mood. However, recent meta-analytical data suggest self-reports and structured interviews yield comparable results in PTSD prevalence, though self-reports may slightly overestimate prevalence 24.

Regarding the sample size, while it is statistically sufficient and representative of the clinical capacity of "Agios Andreas" Hospital, the slight numerical imbalance between Group A and Group B, as a result of facility logistics, may marginally affect statistical power in subgroup analyses. Furthermore, despite utilizing the CALPAS scale, the inherent overlap between method-specific efficacy and the non-specific benefits of the therapeutic alliance remains difficult to decouple—a common challenge in psychotherapy research 25.

Finally, while the findings are representative of the breast cancer population, caution is advised when generalizing to broader demographic contexts. Literature on racial and ethnic minorities show that Black and Asian women are 1.5 to 1.7 times more likely to develop clinical PTSD within two years post-diagnosis, while Latina cancer survivors present higher stress levels than non-Hispanic white women 26. Additionally, recent evidence demonstrates that LGBTQ+ cancer survivors report high risk of impaired quality of life while distress levels are 3-6 times higher than their cisgender, heterosexual counterparts 27. Factors such as cumulative discrimination, healthcare avoidance due to past mistreatment and lack of social support lead to PTSD that is often not just a reaction to the cancer trauma. CAT intervention is theoretically positioned to address these reciprocal roles of the marginalized patient and the powerful medical system.

Results and discussion

PTSD

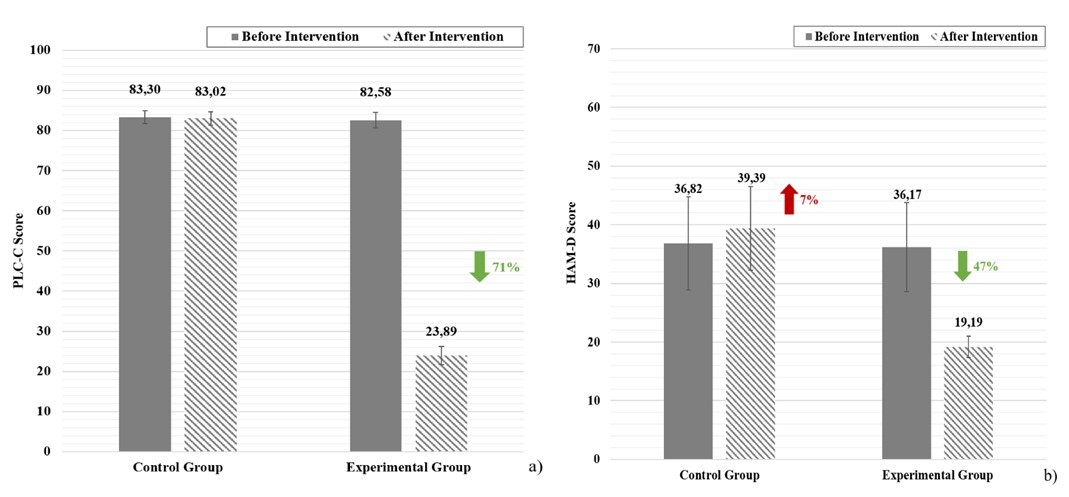

Pre-intervention PTSD scores were elevated in both groups (mean M≈83±1.75, > 44 clinical threshold), reflecting the significant psychological trauma caused by the breast cancer diagnosis (Figure 1a). Women participating in CAT exhibited a substantial reduction in PTSD symptomatology (M=23.89 ± 2.26, 71% decrease), unlike women of the control group whose PLC-C scores remained high (Μ=83.02 ± 1.65), confirming the CAT intervention’s efficacy in lowering trauma-related distress.

Figure 1.a) Average PTSD scale score and b) average HAM-D scale score before and after intervention.

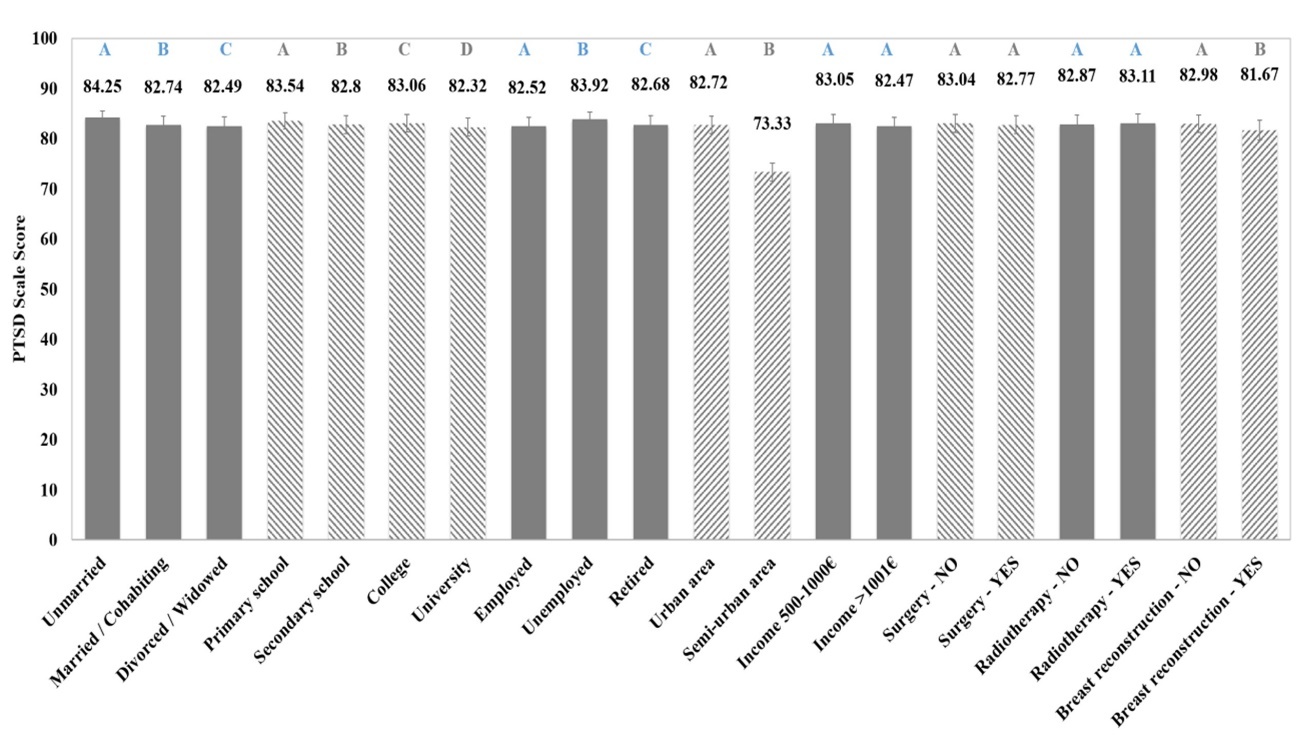

Analysis of demographic, socio-economic and medical variables on both groups pre- intervention, revealed that marital status, education level, employment status, place of residence, breast reconstruction and age showed statistically significant associations with PTSD, though effect sizes were minimal (0.6–2%), whilst income, surgery, radiotherapy, and parity (number of children) were not significant predictors (Figure 2). Although income facilitates a more comfortable lifestyle, the treatment costs for cancer are covered by the Greek national healthcare system. Surgery and radiation therapy procedures provide clinical benefits and a sense of control of the disease, but they remain considerable stress factors due to hospitalization, post-operative recovery and the ongoing risk of cancer recurrence. Finally, the number of children is a factor with a mixed effect, providing strength and emotional support for some women, and acting as an additional emotional and practical burden and maternal role disruption 28, 29, 30.

Figure 2.Effect of the socio-economic and medical factors on the PTSD scale score of women with breast cancer (pre- intervention, N=188). Different letters above bars indicate statistically significant difference at p<0.05 between groups of each factor.

These findings indicate that such factors do not render women with breast cancer more resilient against PTSD, as all participants were similarly vulnerable to trauma from the stage of diagnosis through the initial chemotherapy session.

Depression

The study confirms the high comorbidity between PTSD and depression among women with breast cancer; two mental illnesses that often get misdiagnosed as a result of their overlapping symptomatology (sleep disturbances, anhedonia, and social withdrawal). The mean HAM-D scores pre-intervention indicate clinically significant depression across both patient groups (M≈36.50±7.80), highlighting the substantial psychological burden and the critical need for systematic screening for both PTSD and major depression on women with breast cancer to facilitate early diagnosis and proper therapeutic intervention (Figure 1b). The control group presented a 7% increase in depressive symptoms after the chemotherapy sessions, likely reflecting cumulative psychological and physical strain, fear of cancer recurrence and alterations in body image. These finding are corroborated by recent research, as Hormozi et al. (2019) reported progressive increase in depression and anxiety at 1, 3 and 6 months post-chemotherapy. A systematic meta-analysis by Pilevarzadeh et al. (2019) showed that 32.2% of breast cancer patients worldwide experience depression, while other studies report rates up to 56%, with depression being most common in the first 5 years after diagnosis 31.

The experimental group presented a clinically significant improvement in depressive symptomatology as participants showed a 47% reduction in their mean HAM-D score, which declined to M=19.19±1.83 – a value reflecting moderate levels of depression. CAT, being a structured psychological intervention, can effectively treat breast cancer patients with PTSD and depression comorbidity.

The most strongly identified factors associated with higher vulnerability to depression among women with breast cancer are 31, 32: i) younger age at diagnosis, as women <50 years old experience more intense loss of identity, reproductive concerns, and social isolation, ii) the lack of supportive environment enhances the inability of breast cancer patients to navigate and adapt to the challenges associated with a chronic and life-altering illness, iii) physical symptoms, such as increased pain and persistent fatigue, fluctuate depending on the stage of the disease or treatment, iv) low educational or socioeconomic level as this may imply less advanced coping skills and restricted access to psychological support, v) and history of pre-existing mental illness.

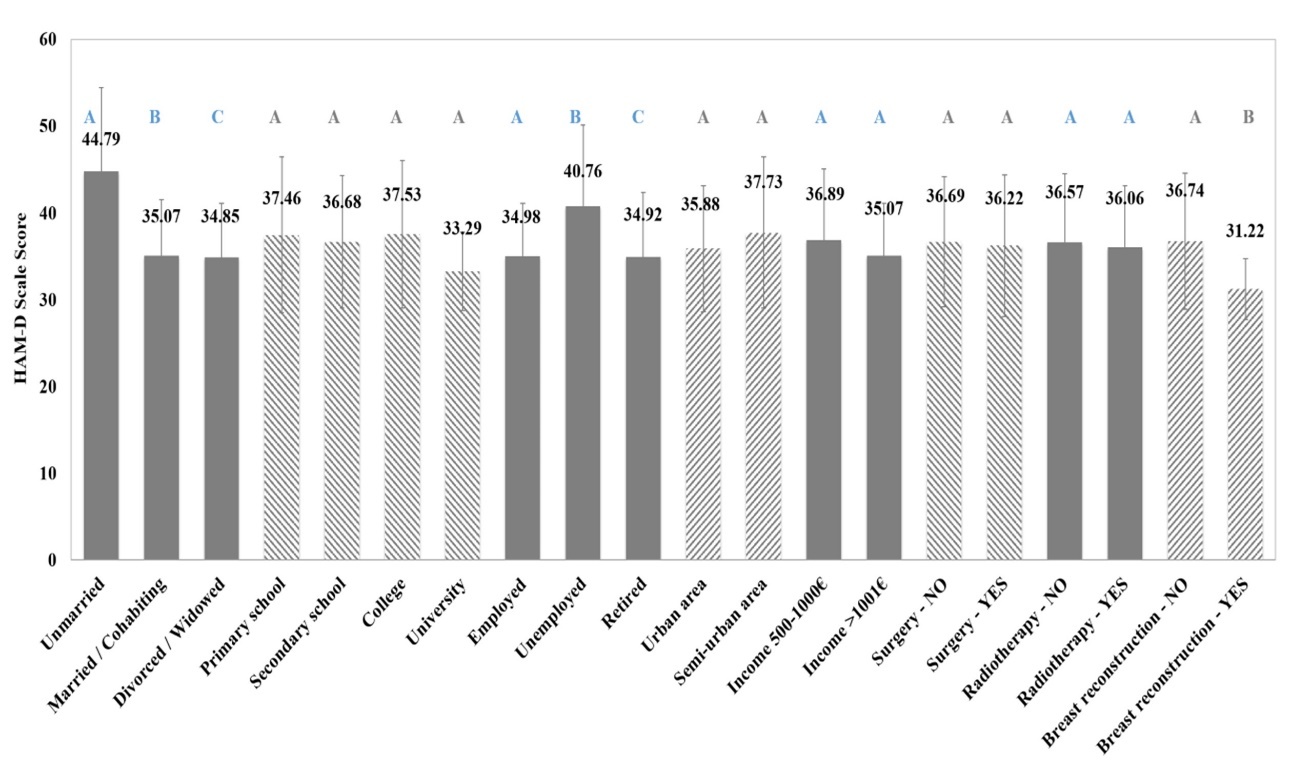

In the present study, the analysis of the socio-economic and medical factors revealed significant associations between depressive symptom levels and the following patient characteristics: marital status, employment status, previous breast reconstruction, age and number of children (Figure 3). The average HAM-D scores for the married/ cohabiting (M=35.07±6.47) and divorced/ widowed (M=34.85±6.28) groups were 27.7% and 28.5% lower, respectively, than for the single women group (M=44.79±9.62). Family status is strongly associated with emotional support/security and financial stability, thus mitigating psychological distress. Nevertheless, the degree to which marital status provides these benefits depends on many factors, such as personality traits, age, the broader support network and the quality and dynamics of human relationships.

Figure 3.Effect of the socio-economic and medical factors on the HAM-D scale score of women with breast cancer (pre- intervention, N=188). Different letters above bars indicate statistically significant difference at p<0.05 between groups of each factor.

Unemployed patients presented approximately 17% higher mean HAM-D score (M=40.76±9.38) compared to employed (M=34.98±6.15) or retired patients (M=34.92±7.43), which is attributed to the uncertainty and instability inherent to the unemployment state, attributes that are intensified by the new conditions that breast cancer diagnosis will inevitably bring to their personal and professional lives. Additionally, the employed and retired patient have potentially already achieved professional validation or possibly have a financial cushioning (savings or pension) enabling a more comfortable adjustment.

Breast reconstruction following mastectomy enables women with breast cancer to redefine their identity and body image as the physical loss of the breast ceases to be outwardly visible and they regain their sense of femininity and sexuality. Patients who underwent breast reconstruction exhibited approximately 15% lower levels of depression (M=31.22±3.53) compared to patients who did not undergo reconstruction (M=36.74±7.84).

Finally, the results showed that two demographic variables, i.e. age and parity present a negative correlation with HAM-D levels, indicating that older women and women with more children report lower depression levels. The role of parity in the psychological well –being of women with breast cancer is widely reviewed and has been proved to be complex and multi- factorial. Having one or two children frequently appears to function as a protective factor against depression, as motherhood can provide emotional support, sense of purpose and strong motivation for recovery 33. On the other hand, women with greater number of children – or those with younger, dependent children – often experience elevated levels of stress, responsibility and guilt 34. These findings highlight the need for a nuanced assessment of the family structure, recognizing that high parity may identify a subset of patients requiring targeted interventions to manage increased emotional load and stress.

On the contrary, the education attainment, place of residence and complementary to the chemotherapy intervention (radiotherapy/surgical procedure) did not demonstrate a statistically significant relationship with depression severity. Similarly, and in line with the pattern observed for PTSD, the income did not emerge as a statistically significant predictor of depressive symptomatology either. The higher education level would be expected to have a protective effect against depression, as it is often associated with enhanced coping resources and reduced vulnerability. However, this buffering influence might have been restricted or masked by high comorbidity between PTSD and depression.

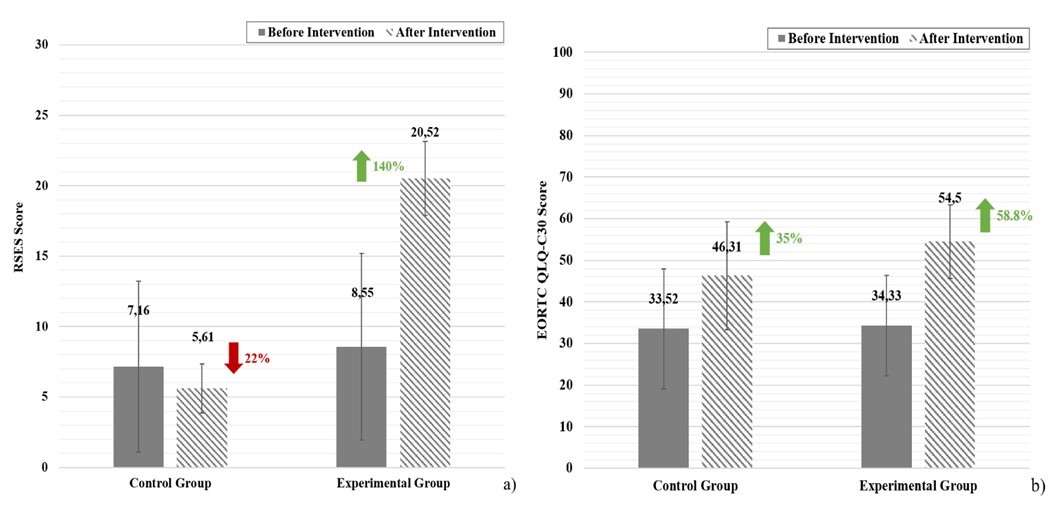

Self-esteem

The analysis of the impact of CAT on the self-esteem of women with breast cancer undergoing treatment showed markedly low self-esteem in both the control group (M=7.16±6.08) and the experimental group (M=8.55±6.62) pre-intervention (Figure 4a). Post- chemotherapy, the control group's self-esteem further deteriorated by 21.7% (M=5.61±1.75), reflecting the significant psychosocial distress from diagnosis, radical reorganization of self- concept and treatment side effects (e.g., mastectomy, alopecia, pain).

Figure 4.a) Average Rosenberg self-esteem scale score and b) average QLQ-C30 scale score before and after intervention.

In stark contrast, the CAT intervention resulted in an extraordinary 140% increase in the experimental group's self-esteem (Μ=20.52±2.62), elevating to moderate/normal self- esteem levels. This improvement is attributed to CAT’s success in enabling patients to recognize and restructure dysfunctional cognitive and relationship patterns, thereby mitigating the internalized roles that maintained self-criticism and promoting self-esteem and psychological resilience.

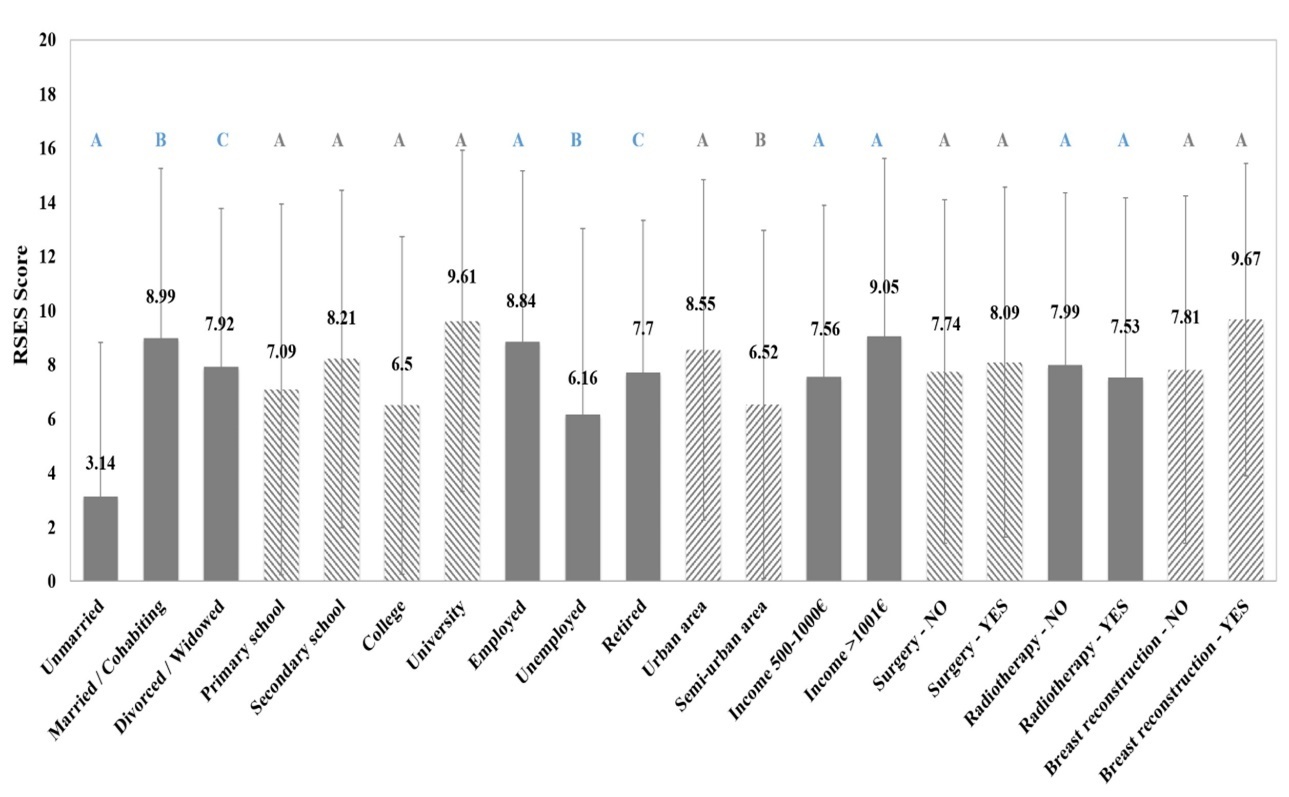

The marital and professional status, place of residence, age and parity all demonstrated a statistically significant impact on self-esteem, however, the self-esteem score is very low in all categories (Figure 5). Specifically, single patients exhibited 60% lower self-esteem score (Μ=3.14±5.68) compared to divorced/widowed (Μ=7.92±5.85) and 65% lower than married/cohabiting patients (Μ=8.99±6.25), as a result of the perceived validation by a supportive partner. Unemployed patients presented 43.5% lower self-esteem score (Μ=6.16±6.87) than employed (Μ=8.84±6.31) and 25% lower than retired patients (M=7.70±5.64). Women living in semi-urban areas presented 23.7% lower self-esteem (M=6.52±6.43) compared to patients from urban areas (M=8.55±6.29). Older age and high parity seems to positively impact self-esteem. Regarding age, older patients reported higher self-esteem than younger patients, potentially due to greater life experience, more mature coping mechanisms, or different life expectations. While literature suggests mixed findings, with some research indicating better body image and higher self-esteem in older women 35 and others finding no statistically significant age-based difference 36, these results indicate age and its associated life maturity may be a protective factor.

Figure 5.Effect of the socio-economic and medical factors on the Rosenberg self-esteem scale score of women with breast cancer (pre-intervention, N=188). Different letters above bars indicate statistically significant difference at p<0.05 between groups of each factor.

Contrary to some findings in the literature 37, 38, 39, no statistically significant effect was observed for any of the following variables on patient self-esteem in the current research: educational attainment, income, surgical intervention, radiotherapy and breast reconstruction. The lack of significance may be attributed to several mitigating factors within the study population, such as PTSD and depression comorbidity, as well as the timing and context of the self-esteem measurement. Furthermore, the immediate or planned availability of free breast reconstruction post- mastectomy, provided by the public hospital, may serve as a mitigating factor. The relief of tumor removal, coupled with the hope of restoring pre-operative breast image, could temper the expected deterioration of self-esteem often associated with disfiguring surgery. Therefore, the effect of these clinical and socioeconomic factors on self-esteem requires further investigation considering complex interactions with variables such as age at surgery, sexual activity, and stage of treatment.

Quality of life

Both groups exhibited similar, low global health status (Quality of Life, QoL) scores (experimental group M=34.33±12.04; control group M=33.52±14.40) prior to intervention, highlighting the significant negative impact of breast cancer on patient’s overall psychological and physical well-being (Figure 4b).

Chemotherapy, while essential for treatment, is associated with a substantial deterioration in quality of life, marked by worsening functional scales (physical and emotional) and increased symptoms such as fatigue, nausea, appetite loss, and financial distress 40. Low QoL scores reflect the physical exhaustion and psychological burden associated with chemotherapy 41. However, after chemotherapy treatment, the control group’s QoL score improved by 35% (M=33.52±14.40 pre- and M=46.31±13.00 post-chemotherapy) marked by the resolution of persistent side effects like nausea, vomiting and alopecia, leading to improved daily life. This improvement aligns with existing literature showing recovery to pre-treatment QoL scores or even higher within 6-12 months post-chemotherapy attributed to adaptation to diagnosis, reduced symptomatology, and increased psychological resilience 42, 40, 43.

The experimental group demonstrated a more substantial improvement, with a QoL score increase of 58.8% (M=54.50±8.82). Although literature linking directly CAT to QoL in cancer is limited, related cognitive-analytic interventions in cancer patients have shown significant improvements in functional scales and symptom reduction 44, 45.

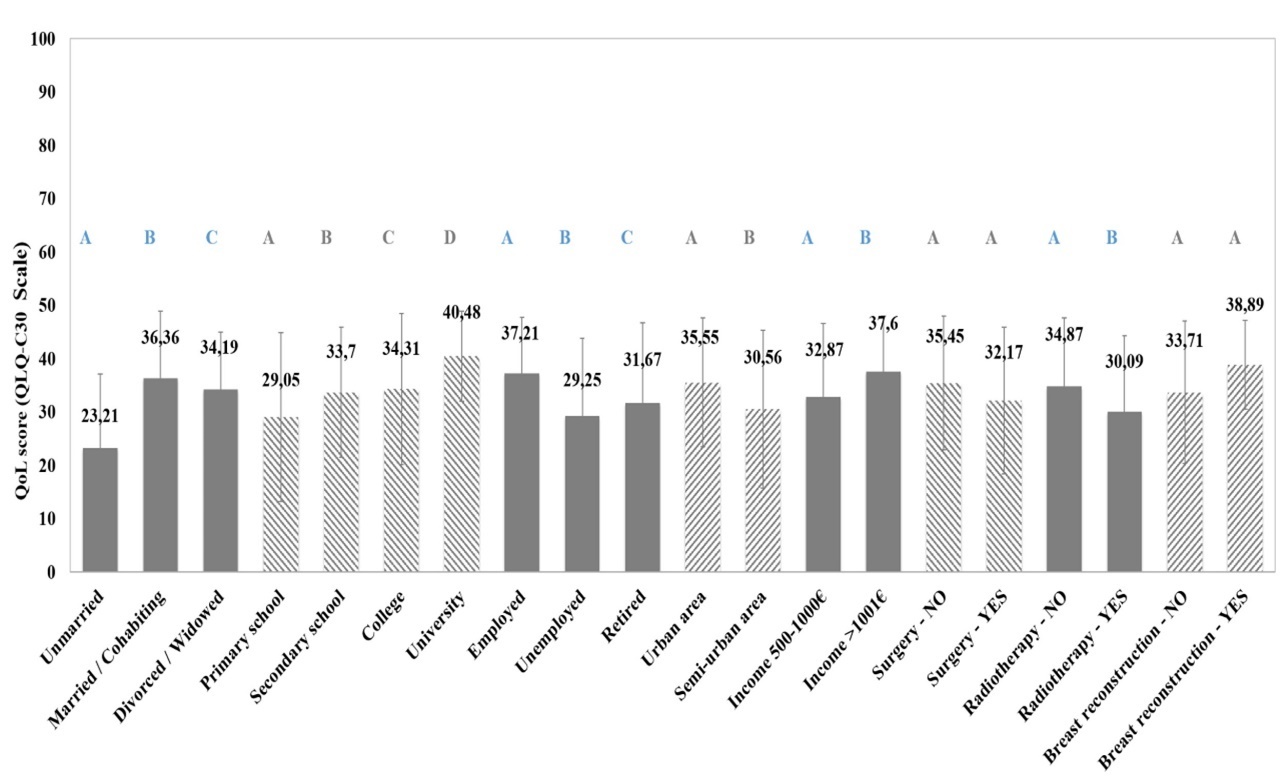

Marital status, education level, employment status, residence area, income and radiotherapy showed statistically significant associations with QoL, while surgical intervention, breast reconstruction, age and parity did not statistically affect QoL levels (Figure 6). Unmarried patients reported significantly worse general health status (M=23.21±13.86) compared to both married/cohabiting patients (M=36.36±12.55) and divorced/widowed patients (34.16±10.78), 36% and 32% worse, respectively. Results demonstrated a positive correlation between higher educational attainment and QoL score as education enhances patient’s capacity to understand the illness, access relevant health information and employ adaptive coping mechanisms for stress, contributing to an improved overall quality of life 41, 46.

Figure 6.Effect of the socio-economic and medical factors on the quality of life score (QLQ-C30 scale) of women with breast cancer (pre-intervention, N=188). Different letters above bars indicate statistically significant difference at p<0.05 between groups of each factor.

Unemployed patients reported a 21% poorer quality of life (M=29.25±14.64) compared to employed patients (M=37.21±10.60) and 15% lower compared to retired patients (M=31.67±15.00), suggesting that employment acts as an important social determinant of well- being. Employment provides a sense of normalcy, social identity and self-efficacy, factors that enhance the overall quality of life 41, while unemployment or early retirement are associated with reduced psychological and social functioning and increased financial insecurities 47. Therefore, maintaining employment or facilitating a return-to-work strategy is a crucial factor for enhancing the QoL of breast cancer patients.

Patients residing in urban areas (M=35.55±12.08) exhibited a 16% better general health status compared to those in semi-urban areas (M=30.56±17.78), likely as a result of easier access to support groups, specialized healthcare services, and social activities, which collectively contribute to a higher quality of life 41.

Income level was found to be a statistically significant determinant of QoL, as patients with a monthly income exceeding 1001€ reported a 14% better general health status (M=37.60±10.35) compared to those in the 500€-1000€ income group (M=32.87±13.74). Furthermore, irradiated patients reported a worse general health status (M=30.09±14.26) compared to those who didn’t receive radiotherapy (M=34.87±12.77). Literature supports that during and immediately following radiotherapy, patients often exhibit reduced physical functioning, increased fatigue, pain, and sleep disturbances, though emotional and social domains are less affected 48, 49. Despite these acute effects, long-term follow-up typically shows a gradual recovery across functional and symptomatic scales, with QoL returning to pre-treatment levels 50, 51.

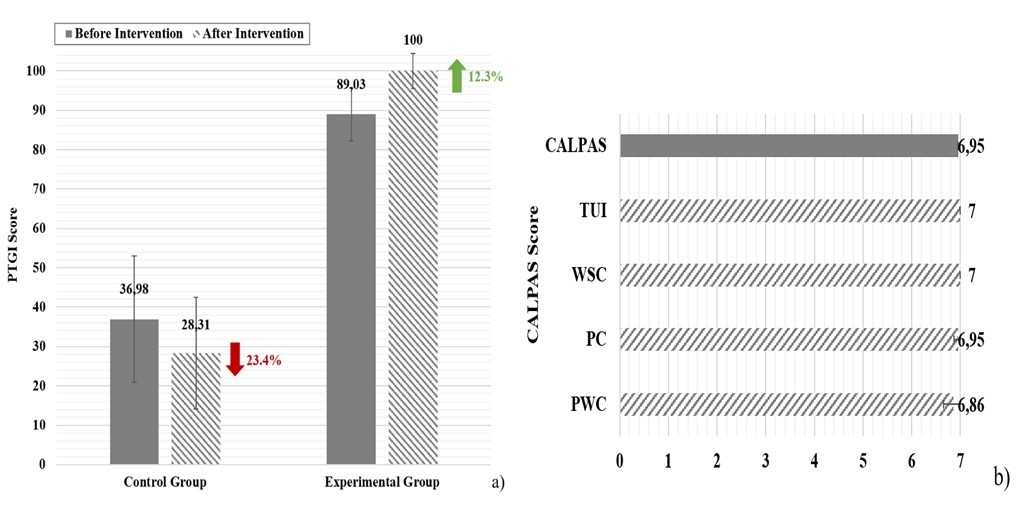

Post-traumatic growth

The control group exhibited low PTGI scores (M=36.98±15.98) which subsequently deteriorated by 23.4% following the completion of chemotherapy (M=28.31±14.20) (Figure 7a). Post-traumatic growth is a complex spiritual and cognitive phenomenon, distinct from psychopathology, that involves the deep realization of life's radical changes and the re- evaluation of core beliefs, ultimately leading to setting of new life goals 52. The lack of psychological intervention and the acute stress of chemotherapy may impede this necessary cognitive reframing process, particularly as growth is highly dependent on individual personality, resilience, spirituality, and social support.

Figure 7.a) Average PTGI scale score and b) average CALPAS score before and after intervention

It is worth noticing that the experimental group showed an unexpectedly high PTGI score prior to intervention (M=89.03±6.70), which subsequently improved by 12.3% after CAT sessions (M=100±4.41). This high pre-intervention score is likely attributed to the anticipation and initial engagement in the therapy process (having already completed two sessions prior to the PTGI measurement). Additionally, the CAT material provided before the sessions (Psychotherapy Booklet and Rating Scale) may have functioned as a cognitive framework, revealing dysfunctional roles, prompting self-awareness, and foreshadowing the possibility of change and control, thereby prematurely activating post-traumatic growth. CAT directly supports the cognitive functions necessary for post-traumatic growth, by improving self- awareness regarding one's relationship with the self and significant others and reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression,. The process of post-traumatic growth —the cognitive appraisal of a traumatic event as an impetus for regeneration—is inherently tied to the individual’s personal history, lifestyle, and coping mechanisms, all of which are targeted and enhanced by the CAT framework.

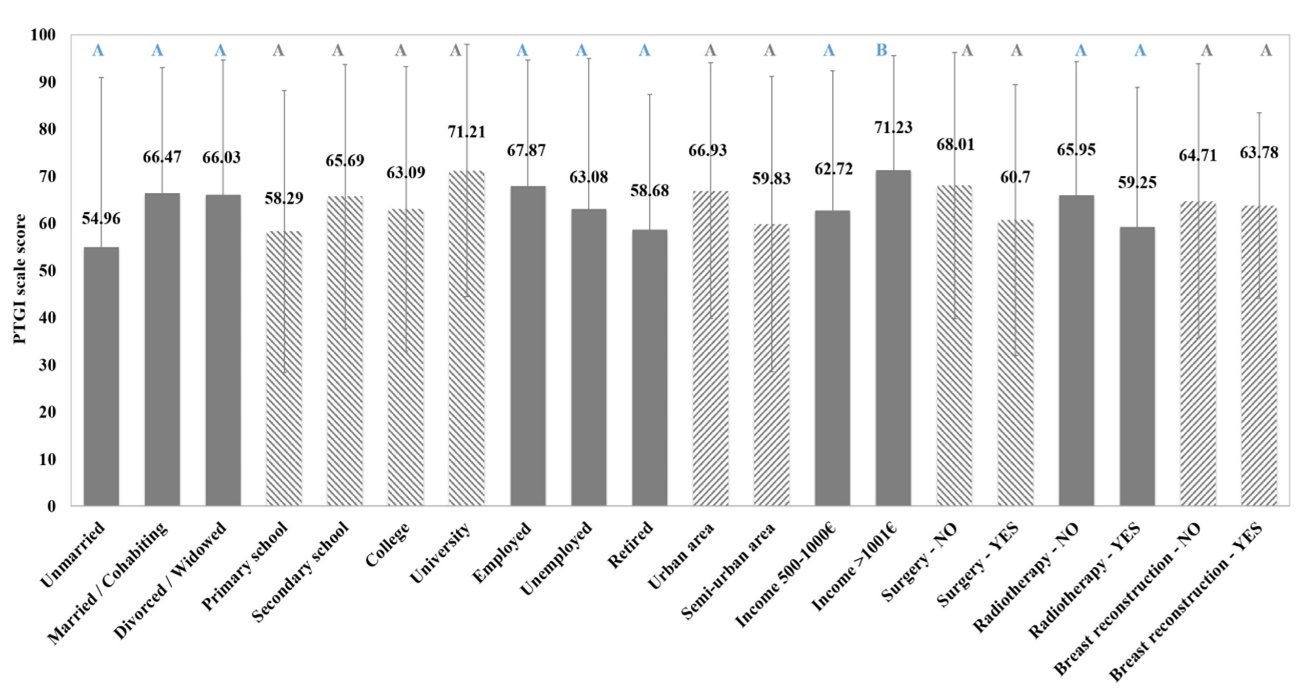

Younger women often demonstrate a more pronounced tendency to develop new coping strategies and experience post-traumatic growth as the disease diagnosis coincides with the zenith of their professional, relational, and family roles, making coping and adapting a necessity rather than an option 52. Moreover, partnership and family life serve as crucial catalysts for post-traumatic growth, providing a sense of continuity and belonging, which allows the cancer experience to be shared, and ultimately fragmented into manageable components 53. Despite the theoretical influence of social factors, the analysis of the studied factors (excluding income) revealed no statistically significant effect on the post-traumatic growth of the breast cancer patients (Figure 8). The single exception was income, which showed a statistical influence (as noted in prior analysis). Post-traumatic growth is a deeply internal and multifactorial phenomenon, and the mechanism of growth is primarily driven by complex individual cognitive and emotional characteristics, including the type of trauma, the time elapsed since the event, and inherent psychological resilience, rather than readily observable external variables.

Figure 8.Effect of the socio-economic and medical factors on the PTGI scale of women with breast cancer (pre-intervention, N=188). Different letters above bars indicate statistically significant difference at p<0.05 between groups of each factor.

Therapeutic relationship

All patients of the experimental group developed very strong therapeutic alliance with the therapist (Figure 7b), reaching the maximum possible score on the overall CALPAS scale and all its subscales (Patient Working Capacity –PWC, Patient Commitment –PC, Working Strategy Consensus –WSC and Therapist Understanding and Involvement – TUI). The quality and strength of therapeutic relationship plays a crucial role as a therapeutic mechanism which fosters trust, provides emotional regulation, and motivates commitment to the treatment plan, thereby directly impacting the effectiveness of the overall therapeutic process.

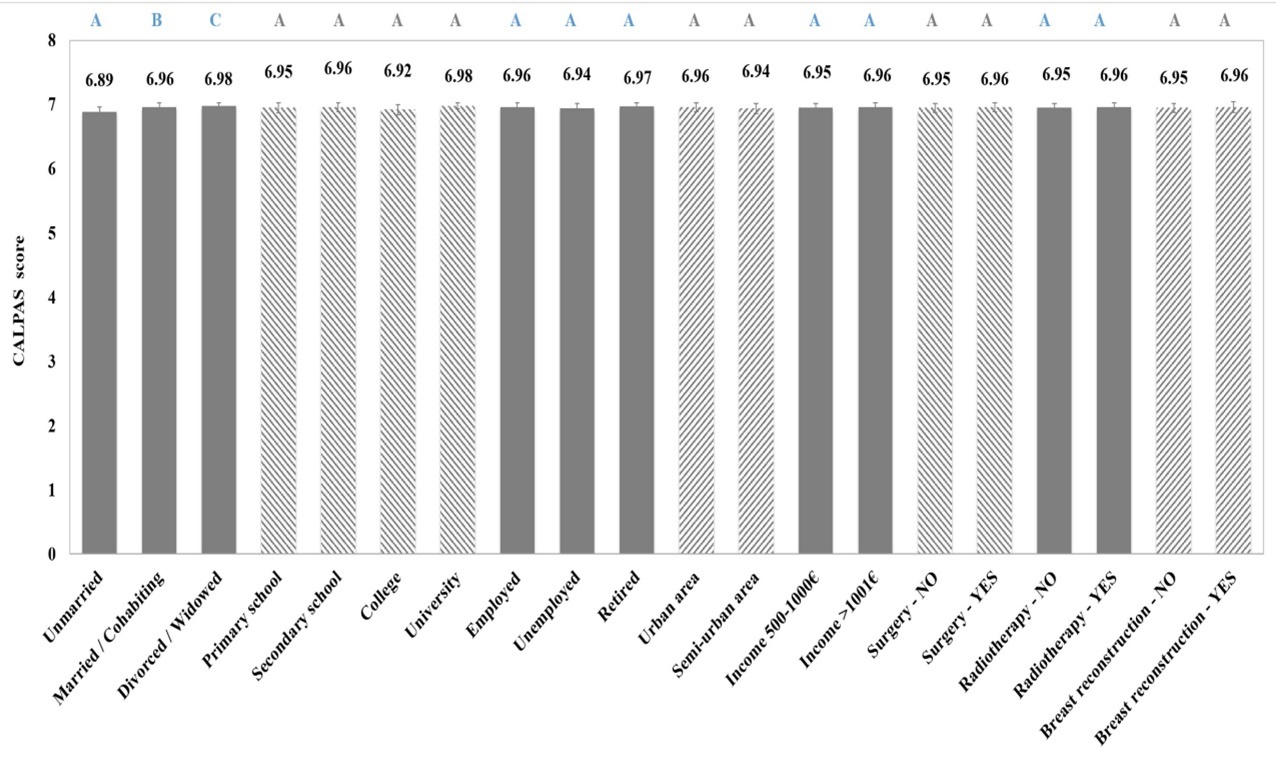

Statistical analysis revealed a statistically significant, though slight, relationship between marital status and therapeutic relationship, as unmarried patients reported marginally higher CALPAS scores (an improvement of 1% to 3.74%) compared to married/cohabiting or divorced/widowed patients (Figure 9).

Figure 9.Effect of the socio-economic and medical factors on the CALPAS score of women with breast cancer (pre- intervention, N=188). Different letters above bars indicate statistically significant difference at p<0.05 between groups of each factor.

Furthermore, older age and a greater number of children were associated with higher patient working capacity and patient commitment scores, and the overall CALPAS scale. Age is linked to greater cognitive and emotional maturity, enhancing the capacity to form trusting relationships and commit to the therapeutic process 54, 55. Similarly, having children is connected to improved emotional management skills, empathy, cooperation, and commitment, all of which contribute positively to the quality of the therapeutic relationship 54. These factors are not direct predictors of the therapeutic relationship quality but function indirectly by influencing the patient's capacity for forming a beneficial therapeutic bond.

On the contrary, educational level, employment status, place of residence, income, surgical or radiation treatment, and plastic breast reconstruction did not statistically significantly affect the CALPAS score. Although higher education is associated with increased communication and reflective skills, and employment with cooperation and self-efficacy 54, 56, these effects did not translate into a statistically stronger therapeutic relationship in this sample. This suggests that while pre-existing skills may predispose patients to strong alliances, the therapeutic setting itself, through the therapist's consistent support, stability, and acceptance, can effectively enhance the therapeutic relationship’s quality, even when these external factors are not initially strong.

Correlation between psychometric scales

The correlation analysis between the psychometric tools (Table 1) revealed that all correlations are statistically significant (p<0.05) except from post-traumatic growth with the therapeutic relationship scale (PTGI – CALPAS). The strongest relationships were observed between the depression and PTSD scale (positive, meaning that patients with highest depression score presented more severe PTSD score), the Rosenberg self-esteem and Hamilton depression scales (negative correlation - patients with depression presented lower self-esteem), the global health status and depression scales (negative - higher HAM-D scores suggest lower QoL), CALPAS therapeutic relationship with depression (negative - higher HAM-D scores suggest weaker therapeutic alliance) and CALPAS therapeutic relationship with Rosenberg self- esteem scale (positive - better quality of life corresponds to stronger therapeutic alliance).

Table 1. Correlation between psychometric scales.| PTSD | HAM-D | ROSENBERG | QLQ-C30 QoL | PTGI | CAPLAS | |

| Spearman’s Rho | ||||||

| PTSD | 1 | |||||

| HAM-D | 0,474 | 1 | ||||

| ROSENBERG | -0,297 | -0,719 | 1 | |||

| QLQ-C30 QoL | -0,431 | -0,666 | 0,481 | 1 | ||

| PTGI | -0,274 | -0,207 | 0,229 | 0,187 | 1 | |

| CALPAS | -0,312 | -0,734 | 0,791 | 0,507 | -0,019 | 1 |

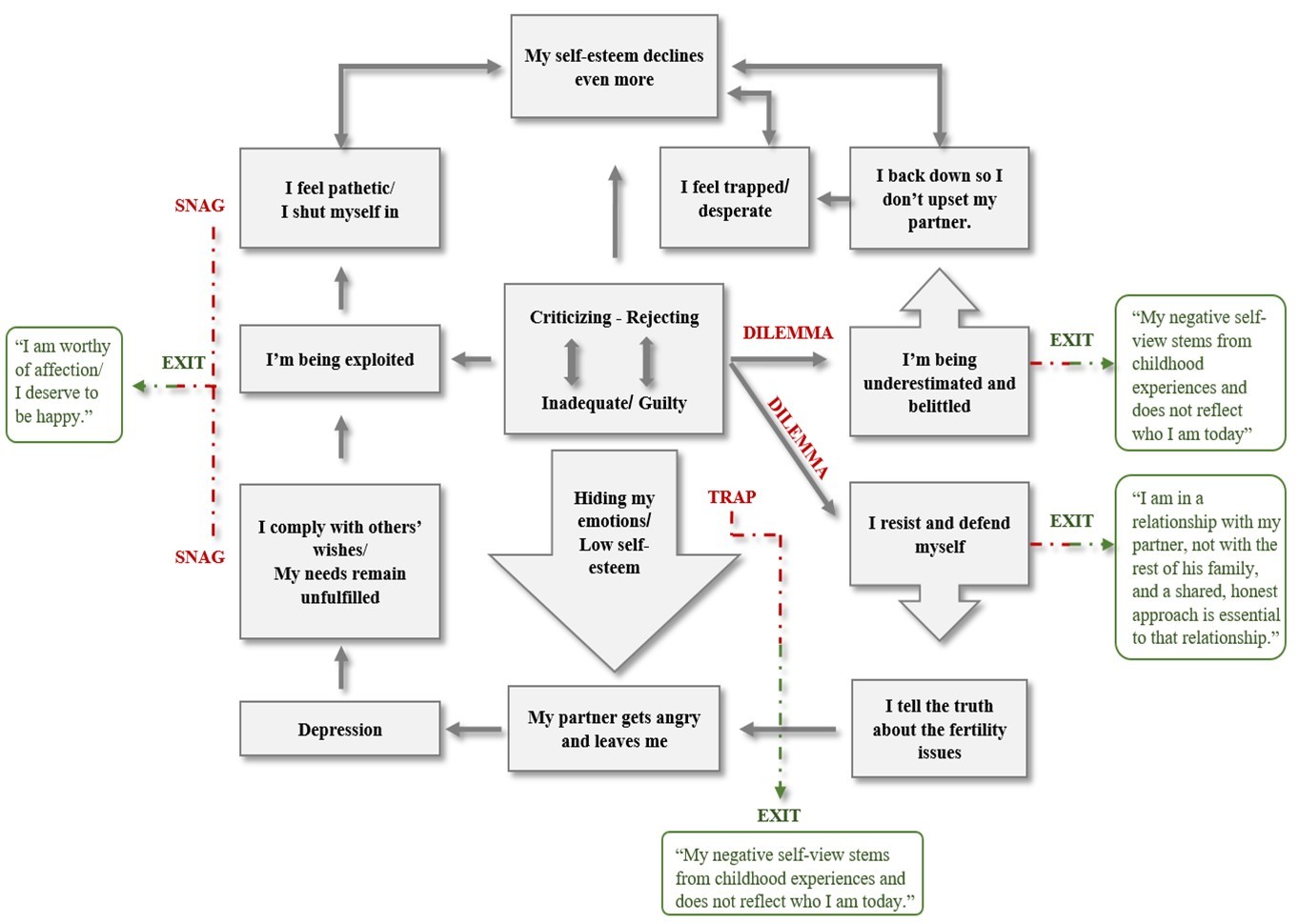

Case Study

CAT focuses on identifying patterns rather than symptoms and these stuck patterns are categorized into Traps (vicious cycles), Dilemmas (false choices) and Snags (self- sabotage). Therapy is structured in three phases: i) reformulation (1st – 5th session) where the patient’s history is explored in CAT terms, the therapist drafts the Reformulation Letter as a narrative of the patient’s story and the Sequential Diagrammatic Reformulation (SDR) is co- created by the patient and the therapist as a visual map of the patient’s ineffective patterns, ii) recognition phase (6th – 12th session) during which the SDR is being analyzed and iii) the revision phase (13th – 16th session), where new and healthy ways of responding are formulated and therapy concludes with the exchange of the Goodbye Letters.

The SDR is the CAT’s map that includes the reciprocal roles, the stuck patterns, the triggers and the exits. For a patient with breast cancer and PTSD, this map moves beyond just symptoms; it visualizes how the cancer trauma - accumulated with the trauma from previously dysfunctional reciprocal roles and behavioral patterns - has exacted their coping mechanisms, sense of self-awareness and their interactions with others. For example, participant Anne M., diagnosed with PTSD and depression, is a 39 years old private sector employee in a 19-year civil union with her partner. Her husband is diagnosed with infertility but refuses to admit it and publicly blames her instead. The active reciprocal role (“parent” role) is critical/rejecting/devaluing while the passive reciprocal role (“child” role) is inadequate/guilty/low self-esteem (Figure 10). The therapeutic process facilitated a shift from a passive and defined-by-others existence to an active, internal locus of control. Through the identification of traps, dilemmas, snags and therapeutic exits, the patient successfully challenged historical patterns of self-neglect and external validation and terminated her own vicious cycle by ending the relationship and focusing on her mental and clinical health and building her happiness from the beginning. Ultimately, the patient reframed the oncological crisis as a catalyst for post-traumatic growth, culminating in a definitive commitment to identity reconstruction and systemic personal change.

Figure 10.Sequential diagrammatic reformulation for a case study of “Critical/Rejecting – Inadequate/Guilty” reciprocal roles.

Conclusions

Breast cancer affects not only women’s physical health but also their psychological well-being. This study confirms that CAT is a highly effective intervention for women with breast cancer and PTSD in reducing post-traumatic stress and depressive symptoms, improving self-esteem and quality of life, achieving greater post-traumatic growth, and fostering a better therapeutic relationship with the therapist. The broader implementation of CAT in women with breast cancer and PTSD is recommended, as it is designed for the national healthcare system, has a short duration, and does not burden the patient or her insurance provider, since it can be applied by any trained psychologist within the hospital setting.

The fear of imminent death is universal among women with breast cancer, regardless of demographic or socio-economic characteristics. There is a measurable relationship between socio-educational parameters, personality traits, and the likelihood that a woman with breast cancer will develop PTSD, thereby impairing her health. However, the onset of PTSD is not explained or predicted solely by a specific factor but rather is the result of the concurrency of multiple factors. Attempt to identify and assess the predisposed factors can help in prevention and early intervention aiming at enhancing resilience, addressing pre-existing mental health conditions and supporting adaptive coping in high risk populations (e.g. women with family history of breast cancer). The high level of comorbidity of PTSD with depression as a consequence of breast cancer must be considered, as well as the inherently varied quality and dynamics of human relationships.

References

- 1.S M Lima, R D Kehm, M B Terry. (2021) Global breast cancer incidence and mortality trends by region, age-groups, and fertility patterns. , EClinicalMedicine 38, 100985-10.

- 2.Iacoviello L, Bonaccio M, G de, Donati M B. (2021) Epidemiology of breast cancer, a paradigm of the “common soil” hypothesis. Seminars in Cancer Biology, Volume 72, Elsevier.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2020.02.010 .

- 3. (1994) American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.) .

- 4.Field T. (2024) Post-traumatic stress disorder research: A narrative review. , Journal of Psychology & Clinical Psychiatry 15(6), 303-307.

- 5.Brunoz P. (2024) Post-traumatic stress disorder and potential biomarkers: A critical review. , Journal of Psychology & Clinical Psychiatry 15(6), 330-335.

- 6.Tang B, Deng Q, Glik D, Dong J, Zhang L. (2017) A Meta-Analysis of Risk Factors for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Adults and Children after Earthquakes. , International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14(12), 1537-10.

- 7.Georgescu T, Nedelcea C. (2023) Pretrauma risk factors and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms following subsequent exposure: Multilevel and univariate meta-analytical approaches. Clinical psychology & psychotherapy, 10.1002/cpp.2912. Advance online publication.https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2912 .

- 8.C R Brewin, Andrews B, J D Valentine. (2000) Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. , Journal of consulting and clinical psychology 68(5), 748-766.

- 9.Haering S, Meyer C, Schulze L, Conrad E, M K Blecker et al. (2024) Sex and gender differences in risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. , Journal of psychopathology and clinical science 133(6), 429-444.

- 10.Guarino A, Polini C, Forte G, Favieri F, Boncompagni I et al. (2020) The Effectiveness of Psychological Treatments in Women with Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. , Journal of clinical medicine 9(1), 209-10.

- 11.Kerr H. (2001) Learned helplessness and dyslexia: A carts and horses issue?. , Literacy 35, 85-10.

- 12.D H Mohr, Cox D. (2001) Multiple sclerosis: Empirical literature for the clinical health psychologist. , Journal of Clinical Psychology 57, 479-499.

- 13.Garyfallos G, Adamopoulous A, Karastergious A, Voikli M, Zlatanos D et al. (2002) Evaluation of cognitive-analytic therapy (CAT) outcome: A 4-8 year follow up. , The European Journal of Psychiatry 16(4), 197-209.

- 14.K L Romm, J I Rossberg, C F Hansen, Haug E, O A Andreassen et al. (2011) Self-esteem is associated with premorbid adjustment and positive psychotic symptoms in early psychosis.BMC. , Psychiatry 11, 136-10.

- 15.Kellett S, Bennett D, Ryle A, Thake A. (2014) Cognitive analytic therapy: A review of the outcome evidence base.Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory. , Research and Practice 87(3), 253-277.

- 16.Taylor P, Rietzschel J, Danquah A, Berry K. (2015) Changes in attachment representations during psychological therapy. , Psychotherapy Research 25, 222-238.

- 18.Calvert R, Kellett S. (2014) Cognitive analytic therapy: a review of the outcome evidence base for treatment. Psychology and psychotherapy. 87(3), 253-277.

- 19.F W Weathers, J A Huska, T M Keane. (1991) PCL‐C for DSM‐IV. Boston: National Center for PTSD – Behavioral Science Division. Greek adaptation:.

- 22.R G Tedeschi, L G Calhoun. (1996) The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. , Journal of traumatic stress 9(3), 455-471.

- 23.Gaston L, C R Marmar. (1993) Manual of California psychotherapy alliance scales (CALPAS). , Montreal:

- 24.Ryle A, Kellett S, Hepple J, Calvert R. (2014) Cognitive analytic therapy at 30. Advances in psychiatric treatment. Advance online publication.https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291724002319 , Psychological medicine 20, 258-268.

- 25.A O Horvath, L S Greenberg. (1989) Development and validation of the Working Alliance Inventory. , Journal of Counseling Psychology 36(2), 223-233.

- 26.Mazor M, Nelson A, Mathelier K, J P Wisnivesky, Goel M et al. (2024) Racial and ethnic differences in post-traumatic stress trajectories in breast cancer survivors. , Journal of psychosocial oncology 42(1), 1-15.

- 28.N E Avis, Levine B, M J Naughton, L D Case, Naftalis E. (2015) Age-related longitudinal changes in depressive symptoms and post-traumatic stress following breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. , Psycho-Oncology 24(1).

- 29.Mehnert A, Koch U. (2007) Prevalence of acute and post-traumatic stress disorder and comorbid depression in breast cancer patients during primary cancer care: A prospective study. , Psycho-Oncology 16(3), 181-188.

- 30.Henselmans I, V S Helgeson, Seltman H, J de Vries, Sanderman R et al. (2010) Identification and prediction of distress trajectories in the first year after a breast cancer diagnosis. Health psychology: official journal of the Division of Health Psychology. , American Psychological Association 29(2), 160-168.

- 31.N Z Zainal, N R, Baharudin A, Z A Sabki, C G Ng. (2013) Prevalence of depression in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review of observational studies. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention:. , APJCP 14(4), 2649-2656.

- 32.Pilevarzadeh M, Amirshahi M, Afsargharehbagh R, Rafiemanesh H, S M Hashemi et al. (2019) Global prevalence of depression among breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast cancer research and treatment. 176(3), 519-533.

- 33.Vahdaninia M, Omidvari S, Montazeri A. (2010) What do predict anxiety and depression in breast cancer patients? A follow-up study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 45(3), 355-361.

- 34.B G Mertz, P E Bistrup, Johansen C, S O Dalton, Deltour I. (2012) Psychological distress among women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer. 3387-3394.

- 35.Álvarez-Pardo S, Paz J A De, Romero-Pérez Montserrat, Portilla-Cueto E, M K et al. (2023) Factors Associated with Body Image and Self-Esteem in Mastectomized Breast Cancer Survivors. International journal of environmental research and public health. 20(6), 5154-10.

- 36.Ashfaq M, Shahzadi K, Zia I, Ilyas Z, Bano S. (2025) A Cross-Sectional Study of Body Image Dissatisfaction and Self-Esteem Among Breast Cancer Patients in Rawalpindi/Islamabad. , Pakistan Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 13(1), 262-271.

- 37.Aprilianto E, S A Lumadi, F I Handian. (2021) Family social support and the self- esteem of breast cancer patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy. , Journal of public health research 10(2), 2234-10.

- 38.Deep S, Swain M, Das S. (2025) Level of Self-esteem and Self-efficacy among Postoperative Breast Cancer Patients. Indian journal of public health. 69(2), 211-213.

- 39.Khemiri S, Boudawara O, Toumi N, Ayedi I, Khanfir A. (2023) Self-esteem following mastectomy in early breast cancer patients. , Journal of Cancer Research & Clinical Practice 6(2).

- 40.Montazeri A, Vahdaninia M, Harirchi I, Ebrahimi M, Khaleghi F et al. (2008) Quality of life in patients with breast cancer before and after diagnosis: An eighteen months follow-up study. , BMC Cancer 8(1), 330-10.

- 41.Fayers P, Bottomley A. (2002) EORTC Quality of Life Group, & Quality of Life Unit. , Oxford, England: 38, 125-133.

- 42.Arndt V, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Brenner H. (2005) Quality of life over 5 years in women with breast cancer after breast-conserving therapy versus mastectomy: A population-based study. , Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology 131(4), 247-254.

- 43.Browall M, Ahlberg K, Karlsson P, Danielson E, Persson L-O et al. (2008) Health-related quality of life during adjuvant treatment for breast cancer among postmenopausal women. , European Journal of Oncology Nursing 12(3), 180-189.

- 44.Moorey S, Greer S. (2012) Cognitive behaviour therapy for people with cancer. ISBN-13 978-0198508663.

- 45.D W Kissane, Bloch S, G C Smith, Miach P, D M Clarke et al. (2003) Cognitive-existential group psychotherapy for women with primary breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. , Psycho-oncology 12(6), 532-546.

- 46.Cheon J, Choi Y, J S Kim, B K Ko, C R Kim et al. (2022) Teachable Moment": Effects of an. , Educational Program on Knowledge and Quality of Life of Korean Breast Cancer Survivors. Journal of cancer education: the official journal of the American Association for Cancer Education 37(3), 812-818.

- 47.Mehnert A. (2011) Employment and work-related issues in cancer survivors. , Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 77(2), 109-130.

- 48.D L Buick, K J Petrie, Booth R, Probert J, Benjamin C et al. (2000) Emotional and Functional Impact of Radiotherapy and Chemotherapy on Patients with Primary Breast Cancer. , Journal of Psychosocial Oncology 18(1), 39-62.

- 49.T J Whelan, Levine M, Julian J, Kirkbride P, Skingley P. (2000) The effects of radiation therapy on quality of life of women with breast carcinoma: results of a randomized trial. Ontario Clinical Oncology Group. , Cancer 88(10), 2260-2266.

- 50.Yucel B, E A Akkaş, Okur Y, A, M F Eren et al. (2014) The impact of radiotherapy on quality of life for cancer patients: a longitudinal study. Supportive care in cancer: official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in. , Cancer 22(9), 2479-2487.

- 51.Hofsø K, Bjordal K, L M Diep, Rustøen T. (2014) The relationships between demographic and clinical characteristics and quality of life during and after radiotherapy: in women with breast cancer. Quality of life research: an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 23(10), 2777-10.

- 52.L G Calhoun, R G Tedeschi. (2004) The foundations of post-traumatic growth: new considerations. , Psychological Inquiry 15(1), 93-102.

- 53.Svetina M, Nastran K. (2012) Family relationships and post-traumatic growth in breast cancer patients. , Psychiatria Danubina 24(3), 298-306.

- 54.Gaston L. (1991) Reliability and criterion-related validity of the California Psychotherapy Alliance Scales–Patient Version. , Psychological Assessment 3(1), 68-74.

- 55.Haddock G, Lewis S, Bentall R, Dunn G, Drake R et al. (2006) Influence of age on outcome of psychological treatments in first-episode psychosis. , British Journal of Psychiatry 188(3), 250-254.

- 56.A G Hersoug, Høglend P, J T Monsen, O E Havik. (2001) Quality of working alliance in psychotherapy: therapist variables and patient/therapist similarity as predictors. The Journal of psychotherapy practice and research. 10(4), 205-216.

- 57.Bachelor A, A O Horvath. (1999) The therapeutic relationship in context: Patient and therapist perspectives. , Psychotherapy Research 9(4), 393-405.

- 58.Delsignore A, Rufer M, Moergeli H, Emmerich J, Schlesinger J et al. (2014) California Psychotherapy Alliance Scale (CALPAS): Psychometric properties of the German version for group and individual therapy patients. , Comprehensive Psychiatry 55(3), 736-742.

- 59. (1995) European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). , Quality of Life Group 3-0.

- 60.Hormozi M, S M Hashemi, Shahraki S. (2019) Investigating Relationship between Pre- and Post- Chemotherapy Cognitive Performance with Levels of Depression and Anxiety in Breast Cancer Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP. 3831-3837.